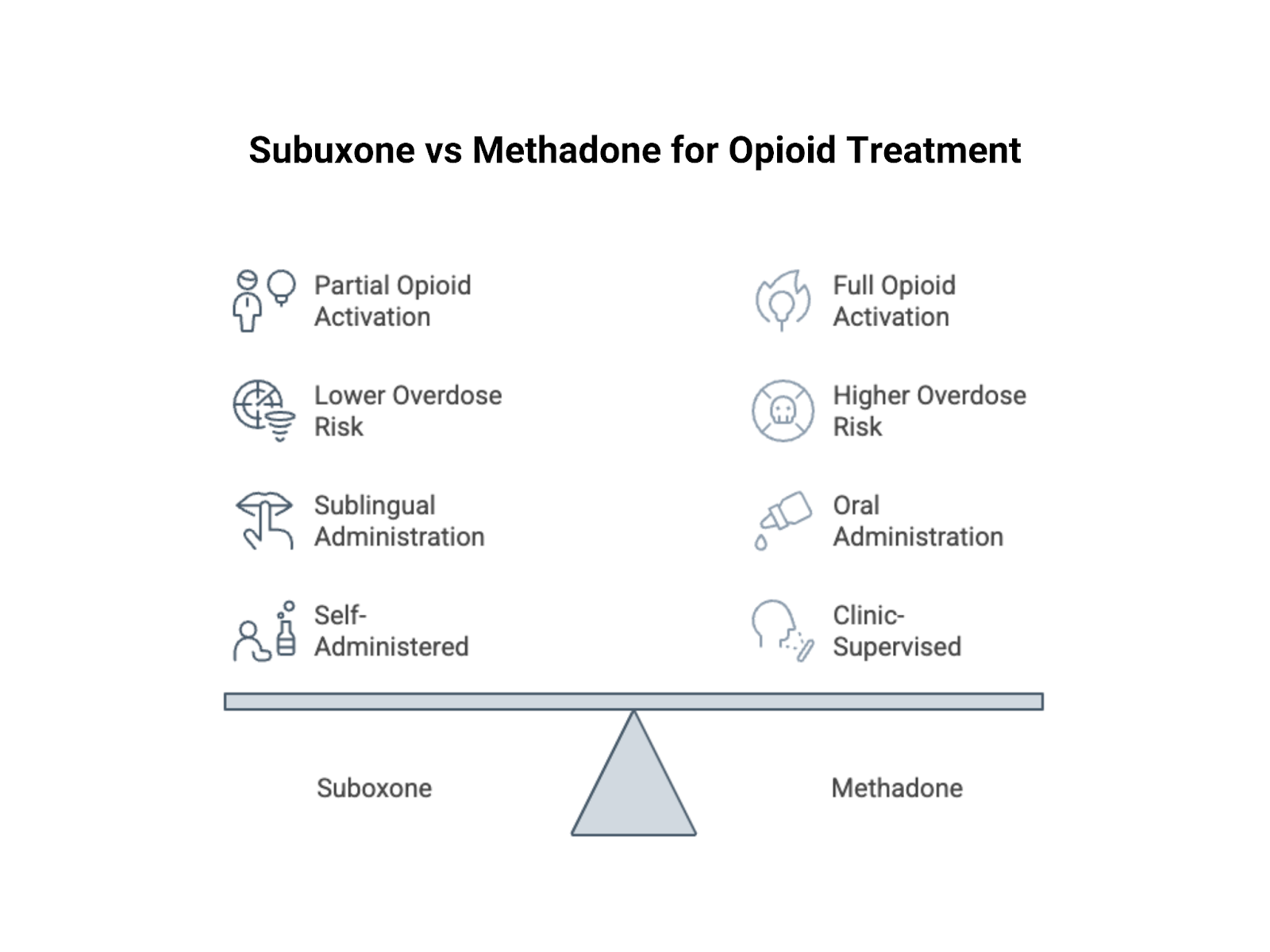

Two medications save lives every day in the fight against opioid addiction, but they work in very different ways and come with distinct rules, risks, and levels of flexibility. Suboxone and methadone are the primary treatments used to manage opioid dependency. Suboxone contains buprenorphine and naloxone, while methadone is a full synthetic opioid. Buprenorphine is a partial agonist, whereas methadone is a full agonist, and that distinction carries meaningful clinical differences.

Suboxone is often prescribed in office based settings and may allow take home dosing, while methadone typically requires daily visits to a specialized clinic, especially early in treatment. Buprenorphine has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression, which lowers overdose risk at higher doses, while methadone does not have that same ceiling. On the other hand, methadone can provide stronger suppression of cravings and withdrawal for some individuals with severe or long standing opioid use disorder. Choosing between them is rarely straightforward. The decision depends on the severity of addiction, prior treatment history, medical considerations, daily responsibilities, and what a person can realistically maintain over the long term. Understanding how these medications differ helps you make an informed choice about the path that best supports sustained recovery.

Suboxone contains two active compounds. The first is buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist that binds to the same receptors as heroin or fentanyl but activates them only partially. This reduces cravings and prevents withdrawal without producing the full euphoric effect associated with other opioids. The second compound is naloxone, an opioid antagonist included primarily to deter injection misuse.

Because buprenorphine is a partial agonist, it has what is known as a ceiling effect. After a certain dose, taking more does not significantly increase the opioid effect, which lowers the risk of respiratory depression and overdose. Buprenorphine also binds tightly to opioid receptors without fully activating them, meaning that if you take another opioid while on Suboxone, much of its effect will be blocked. Suboxone is typically dispensed as a film that dissolves under the tongue and is most often taken once daily. It is prescribed by a qualified clinician, and in many cases patients are allowed to take it home and manage their doses as directed.

Methadone is a full opioid agonist, meaning it binds to and fully activates opioid receptors in the brain. This allows it to completely suppress withdrawal symptoms and significantly reduce cravings. Because it is a full agonist, it carries overdose risks similar to other opioids, especially if misused or combined with other sedating substances.

Methadone has a long half life, with a single dose lasting approximately twenty four to thirty six hours. That steady level in the body prevents the sharp peaks and crashes associated with shorter acting opioids. When properly dosed, it does not produce a high. Instead, it allows people to feel stable and function normally. It is typically dispensed as a liquid with a sweet, medicinal taste and taken orally at a licensed clinic under supervision. Clinic staff control the dosing and observe patients as they take it. Only after demonstrating consistent stability over time can individuals earn take home doses.

How you access these medications can significantly shape your daily life. The structure of treatment often determines whether care integrates smoothly into your existing responsibilities or whether your schedule and routines must revolve around the demands of the program.

Suboxone treatment is typically provided in standard medical offices, where you see a doctor who writes a prescription that you fill at a regular pharmacy. In many ways, it resembles the management of another chronic medical condition, with appointments that may be weekly at first and then spaced out to monthly visits as stability improves. Methadone treatment operates differently and is delivered through specialized opioid treatment programs that are regulated at the federal level. It cannot be dispensed through a regular pharmacy, and patients must enroll in a licensed clinic to receive it. These clinics are often limited in number and may require long commutes, with some individuals traveling significant distances or relying on early morning public transportation.

The clinic model provides structure and accountability, as staff monitor progress, conduct urine testing, and require participation in counseling. For some people, this level of oversight is beneficial. For others, especially those living far from a clinic or without reliable transportation, the structure can create substantial barriers to accessing consistent care.

Methadone treatment typically begins with daily observed dosing, meaning you report to the clinic each morning, wait in line, and take your medication under staff supervision. This schedule usually requires attendance at least six days per week. As you demonstrate stability through consistent participation and negative drug screens, you gradually earn take home doses, though that process can take months and sometimes years.

Suboxone, by contrast, is prescribed in take home quantities from the outset. Patients may receive a week, two weeks, or even a month of medication, depending on clinical judgment, and are responsible for managing their doses independently. That built in flexibility can make a significant difference for individuals trying to maintain employment, care for children, or preserve a sense of normalcy and autonomy during recovery.

Both medications carry risks. But the risks differ in kind and degree.

Buprenorphine’s partial agonist property gives it a ceiling effect on respiratory depression, meaning that even at higher doses it does not suppress breathing to the same degree as full opioid agonists. Fatal overdose from buprenorphine alone is uncommon, particularly when it is taken as prescribed. Methadone does not have this ceiling. As a full agonist, higher doses produce progressively greater respiratory suppression, and although there is a therapeutic range, the margin between an effective dose and a dangerous one is narrower. Methadone related overdoses occur each year, sometimes because individuals take more than prescribed, sometimes because they overestimate their tolerance, and sometimes because the medication accumulates in the body during the early weeks of treatment.

For this reason, the ceiling effect can make Suboxone a safer option for certain patients, including those with underlying respiratory conditions, those at risk of taking extra doses, or those living in unstable environments where medication misuse is more likely.

Methadone can cause dangerous respiratory depression, particularly during the first one to two weeks of treatment while the dose is still being adjusted. The risk increases significantly when it is combined with benzodiazepines or alcohol, and this danger is well documented. Buprenorphine carries a lower risk of respiratory suppression because of its ceiling effect, but that risk is not zero. Combining it with benzodiazepines or alcohol can still lead to serious breathing problems. It is also important to understand that the naloxone in Suboxone does not protect against respiratory depression caused by buprenorphine itself. Naloxone is included primarily to deter injection misuse, not to counteract buprenorphine’s effects when taken as prescribed. Both medications require close medical supervision and careful use. The key difference lies in the margin for error, which is narrower with methadone and somewhat wider with buprenorphine, though neither is without risk.

Studies show that both medications are effective treatments for opioid use disorder. Each reduces illicit opioid use more effectively than no medication, lowers the risk of overdose death, and improves overall quality of life. Some research suggests that methadone may have a slight advantage for individuals with severe, long term addiction. Because it is a full agonist, it can provide stronger receptor activation and may suppress cravings more effectively in people with high opioid tolerance who need that level of stabilization.

Other studies indicate that Suboxone is equally effective for many patients, particularly those with less severe dependence. When comparing broader populations, overall outcomes are often similar, although individual responses can differ significantly. The reality is that neither medication works perfectly for everyone. Some individuals stabilize more successfully on methadone, while others respond better to Suboxone. It is not uncommon for someone to try one medication without success and later achieve stability with the other.

Methadone programs generally demonstrate higher retention rates, with more patients remaining in treatment longer compared to those taking buprenorphine. That difference may suggest methadone is more effective for certain individuals, or it may reflect the added accountability created by the structured clinic model.

Suboxone’s flexibility can be both an advantage and a limitation. The ability to manage medication independently supports autonomy and makes treatment easier to integrate into daily life, yet it can also make it easier for some individuals to discontinue care impulsively. Ultimately, what matters most is sustained engagement and stable recovery, and both medications are capable of supporting that outcome when used appropriately.

Every medication has side effects. Every opioid creates dependence. These facts don't change whether the opioid is treating addiction or causing it.

Both medications create physical dependence. Stop taking them suddenly and you'll experience withdrawal. But the withdrawal differs. Methadone withdrawal is often more severe and longer-lasting. Because methadone has a long half-life, withdrawal symptoms can persist for weeks. The acute phase might last ten to fourteen days. Lingering symptoms can continue for months. Buprenorphine withdrawal is generally less severe. Still uncomfortable. Still characterized by muscle aches, insomnia, anxiety. But often more manageable. The partial agonist effect means the body's dependence is less complete. Neither withdrawal is pleasant. Both can be tapered gradually to minimize symptoms.

Taking these medications means accepting physical dependence. This is not the same as addiction. Dependence is the body's adaptation to a substance. Addiction is compulsive use despite harm. Both methadone and Suboxone create this adaptation. Your opioid receptors adjust to the medication's presence. Stopping means readjustment. Some people stay on these medications for years. Decades. This bothers some people philosophically. But if the medication allows a functional life when without it you'd be using street drugs or dead, the dependence seems a reasonable trade.

Treatment has to fit into your life. If it doesn't, you won't sustain it. The practical details matter as much as the pharmacology.

Suboxone fits more easily into conventional life structures. You see a doctor. You get a prescription. You go to work. You come home. Your employer doesn't need to know. Your children don't see you in clinic lines. This flexibility helps people maintain employment. It helps parents manage childcare. It helps students attend classes. Methadone's clinic requirements create complications. Early morning dosing conflicts with early shifts. Daily attendance is difficult with unpredictable schedules. Business travel becomes nearly impossible until you earn take-homes. But that structure helps some people. The daily routine creates stability. The counseling ensures support. For people whose lives lack structure, the clinic provides it.

Standing in line at a methadone clinic is visible. Everyone knows why you're there. Some clinics are in rough neighborhoods. The waiting areas can be chaotic. This visibility carries stigma. Neighbors might see you. Employers might find out. The association marks you as an addict in a way private medical treatment doesn't. Suboxone treatment is more discreet. It looks like any medical appointment. You control the information. You decide who knows. For people in recovery, this privacy can be protective. It allows rebuilding life without constant reminders of past addiction.

There is no universal answer. The right medication depends on your specific situation, history, and needs.

Severe, long standing opioid addiction may respond better to methadone. If you have been using high doses for years, buprenorphine may not provide enough receptor activation, and the partial agonist effect could leave cravings only partially controlled. Multiple relapses while taking Suboxone can be a sign that you may benefit from methadone’s stronger full agonist effect and the added structure of a clinic setting. On the other hand, if methadone has not worked for you, Suboxone’s flexibility and office based model may offer a better fit. Individuals with less severe or more recent dependence often respond well to buprenorphine, which can fully suppress withdrawal and cravings while carrying a lower overall risk profile.

Your medical history also plays a role. Respiratory conditions may favor Suboxone because of its ceiling effect on breathing suppression, while methadone requires careful cardiac monitoring since it can affect heart rhythm. Legal circumstances can influence access as well, particularly if regular clinic attendance is difficult or if local systems show preference for one medication over another.

Practical realities matter. If you have reliable transportation, stable housing, and a flexible schedule, the structure of a methadone clinic may be manageable or even beneficial. Without those supports, Suboxone’s prescription model may be more sustainable. For individuals caring for children or others who depend on them, the flexibility of Suboxone can make it easier to meet responsibilities while staying engaged in treatment.

Suboxone and methadone both work. Both save lives and make long term recovery possible. The question is not which medication is universally better, but which one fits your needs. Methadone offers stronger craving suppression and built in structure, though it requires clinic attendance and carries a higher overdose risk. Suboxone offers greater flexibility and a wider safety margin, though it requires more self management and may not control severe cravings as effectively for some individuals.

The right choice depends on your addiction severity, medical history, life circumstances, and what you can realistically sustain over time. Talk with a physician or addiction specialist, weigh your options carefully, and commit to the plan you choose. Neither path is effortless, but both offer a real opportunity for recovery.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing eli mattis sit phasellus mollis sit aliquam sit nullam neque ultrices.